by Sebastien GOULARD

The Netherlands continues its policy of returning artworks acquired during the colonial era to Indonesia. In October 2025, the Dutch government returned items from the Dubois collection to Indonesia. This collection, assembled by physician, anthropologist, and paleontologist Eugène Dubois (1858–1940), comprises over 28,000 fossils acquired during his stays in the Dutch East Indies at the end of the 19th century. Among these fossils are the bones of the “Java Man,” which Dubois believed to be the missing link between apes and humans. Java Man was later classified as part of the Homo erectus species. Previously housed at the Naturalis Museum in Leiden, these fossils had been requested by newly independent Indonesia as early as the 1950s. Their return marks a major milestone in cultural cooperation between the Netherlands and Indonesia, due to the significance of the items involved.

A Long and Challenging Process

In 2022, the two countries signed a restitution agreement. The following year, the Netherlands returned several items to both Indonesia and Sri Lanka. In 2024, this agreement enabled the repatriation of over 280 artifacts, including several Buddha statues. These pieces are now on display at the National Museum of Indonesia. However, the agreement goes beyond restitution and also includes a transfer of expertise regarding the conservation and public presentation of the artworks.

Other Western countries have also begun similar restitution processes, not only toward Indonesia but especially toward African nations. In some cases, these efforts are hindered when the items in question are owned not by the state but by private collectors, who may oppose their return.

Western institutions—both public and private—may view such processes with suspicion, as they threaten the integrity of their collections and shed light on past practices that are now seen as ethically questionable. These concerns often prompt public relations efforts aimed at mitigating reputational damage. For example, in the case of the Dubois collection, it is important to note that the excavations which led to the discovery of Java Man were conducted using forced labor under Dutch colonial rule. The restitution process compels Western nations to confront and disclose some of the darkest aspects of their colonial histories.

Since the independence of former colonies in Asia and Africa, demands for restitution have increased—but only in recent years have Western states begun to take them seriously. The Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and France have all established mechanisms to facilitate these returns. On the one hand, these countries have had to acknowledge the injustice of collections acquired through looting. On the other, countries in the Global South have had to build the necessary infrastructure and ensure the proper conditions to receive and protect the returned artifacts.

A large number of pieces displayed in Dutch museums were acquired under dubious circumstances—often the result of looting. For the Netherlands, as for other former colonial powers, the challenge now is to ensure these works are returned under the best possible conditions. That said, the role of the former colonizers ends there. While cooperation agreements may include support for the curation and promotion of these works, it is ultimately up to the receiving country—the rightful owner of this heritage—to decide how these artifacts are to be used or displayed.

In December 2022, the German government returned several bronzes to Nigerian authorities. These had been looted by British troops during a punitive expedition in 1897. However, controversy soon arose over the intended recipients of the returned bronzes: should they be handed over to the descendants of the Oba royal family or to the Museum of West African Art in Benin City? For many Nigerians, this was an internal matter, and former colonial powers should have no say in the debate.

In the case of Indonesia, the issue of protecting the returned artifacts has been raised in various media outlets due to reports of thefts from Indonesian museums. If there are security concerns, it is up to Indonesia to address them, and one can be confident that the authorities are fully committed to safeguarding their cultural heritage.

A Win-Win Partnership

The Netherlands is currently the leading European investor in Indonesia, accounting for nearly 46% of total European investment in the country. In June 2025, the Netherlands announced new investments totaling $300 million in projects aligned with Indonesia’s various development programs. In addition, the Netherlands hopes to benefit from the new free trade agreement signed between the European Union and Indonesia in October 2025.

The Dutch government’s decision to return these fossils contributes to the strengthening of ties between the two nations, in the context of deepening relations between Europe and Indonesia. Although largely symbolic, such gestures create opportunities for future cultural collaborations between the Netherlands and Indonesia. It is worth noting that Jakarta is not currently seeking the return of all Indonesian works held in Dutch institutions—only a portion of them. The items that remain in Dutch museums continue to serve as powerful tools of Indonesian soft power.

For Indonesia—as for other formerly colonized nations—the issue of restitution is threefold. First and foremost, it is a matter of sovereignty: every state should have control over its own heritage and history. Today, according to the IMF, Indonesia ranks as the world’s 17th largest economy, ahead of its former colonizer, which now ranks 18th. Jakarta has the means to preserve, protect, and promote its heritage on its own terms.

Restitution is also a political issue. It enables Indonesian leaders—especially President Prabowo Subianto—to position themselves as defenders of national history and to rally the Indonesian people around a shared identity. This is particularly important in the context of political unrest that has affected the country since the summer of 2025.

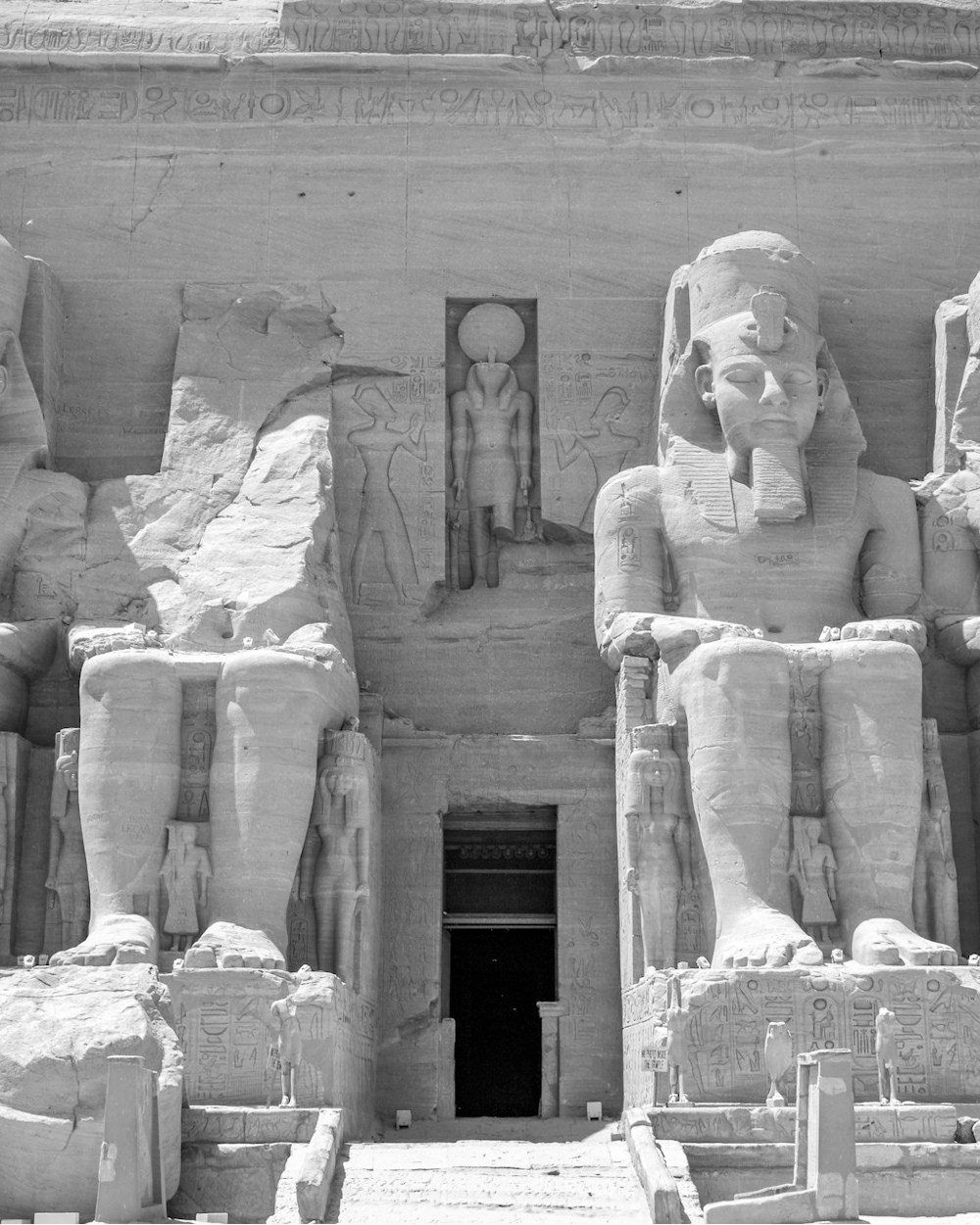

Finally, restitutions serve as a lever for boosting cultural tourism. This goal is shared by many nations looking to diversify their tourism sectors and move upmarket. It is also one of Egypt’s objectives, as the country seeks the return of iconic items such as the Bust of Nefertiti, currently in Berlin, and the Rosetta Stone, held by the British Museum. These globally renowned masterpieces would significantly enhance the profile of Cairo’s new Egyptian Museum.

Indonesia finds itself in a similar position and needs major works—like the Java Man fossils—to build a compelling cultural, artistic, and tourism narrative. The cultural cooperation between the Netherlands and Indonesia will likely be closely watched by other countries hoping to achieve similar success in addressing the challenges of artistic restitution.

Sebastien GOULARD

Sebastien Goulard is a consultant at Cooperans, a consultancy specializing in international relations.

He is also the founder of Diplomarty.

Sebastien Goulard holds a doctorate in economic and social development from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences), Paris. He has been involved in several European research programs focusing on sustainable urbanization in China.